Blade Runner, director Ridley Scott‘s immediate follow-up to Alien (talk about a one-two punch), remains to this day a highly divisive film. The mere fact that there are seven different cuts in circulation doesn’t exactly help (more on that later). If there is one inarguable point of praise that spans both its proponents and detractors, it’s that the film is a world-building, visual masterpiece. It’s influence is far reaching and it continues to inspire science fiction to this day: from anime (the original Ghost in the Shell) to films (The Matrix; The Fifth Element) to television (HBO’s reboot of Westworld; the acclaimed Battlestar Galactica remake – which also starred Runner‘s Edward James Olmos), and video games (Mass Effect).

Blade Runner, director Ridley Scott‘s immediate follow-up to Alien (talk about a one-two punch), remains to this day a highly divisive film. The mere fact that there are seven different cuts in circulation doesn’t exactly help (more on that later). If there is one inarguable point of praise that spans both its proponents and detractors, it’s that the film is a world-building, visual masterpiece. It’s influence is far reaching and it continues to inspire science fiction to this day: from anime (the original Ghost in the Shell) to films (The Matrix; The Fifth Element) to television (HBO’s reboot of Westworld; the acclaimed Battlestar Galactica remake – which also starred Runner‘s Edward James Olmos), and video games (Mass Effect).

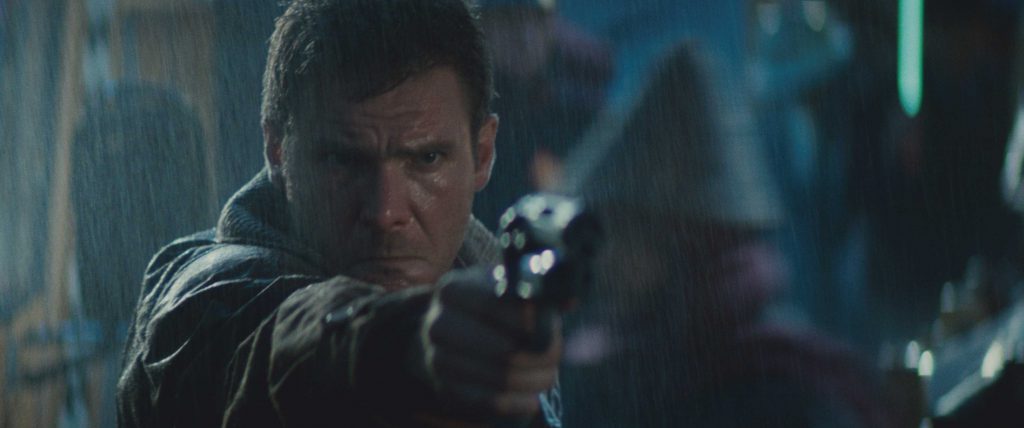

Set in the distant future of 2019, ex-blade runner Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is drummed back into the police force with the task of tracking down and eliminating a handful of escaped replicants – artificial life forms that are human in every way save biology. Led by the incomparable Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), the replicants are on a quest to meet with their reclusive creator, the assiduous Dr. Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel) – but are their motives genial or deadly?

Blade Runner is impressive in a number of ways: the aforementioned cinematography and special effects, Rutger Hauer’s turn as the desperate and dubious antagonist (he reportedly wrote all his own monologues!), Vangelis‘ score (practically performed solo in a direct, emotional reaction to the action on screen), and the engrossing theme of what does it truly mean to be human. On the other hand, one cannot disparage viewers who find the film to be a bit of a slog to sit through (a bizarre thought considering the title has the word “run” in it). It certainly does drag at times – notably one extended scene featuring Ford staring at a monitor blow up of a photograph repeating “enhance, enhance, enhance” over the course of minutes (arguably to the point where the film could have benefited from the very definition of the word).

It’s telling that the film took seven iterations to get to the director-approved final cut. There’s a plethora of potential available but even the final cut is missing the connective tissue to assemble a fully developed, comprehensive motion picture. The theatrical version attempted to bridge this narrative gap by plugging in an unnatural voice over to complement its neo-noir nature. Unfortunately, the final result didn’t quite gel with the rest of the production, appearing quite alien within the framework of the picture (Ford contemplating randomly about sushi prompts more laughs than adequately providing effective character background). The final cut omits this narration, but suffers a loss of pacing and sensible narrative progression as a result.

When fans claim that multiple viewings are a must in regards to Blade Runner, they have a point. This is a prime example of a movie that garners appreciation with every screening – one half in response to the ambiguous nature of the ending, and the other to fully understand how Ford is connecting the dots without the training wheel nature of the original voice over. The final cut is debatably the superior version but suffers from Ridley Scott’s ill-thought attempt to conclusively answer the film’s biggest mystery.

[Major Spoilers Ahead.] Specifically, the question of whether or not Deckard is in fact a replicant himself (to be noted, the sequel may take this in a different direction). Scott’s take is straight forward (and antithetical to Harrison Ford’s own viewpoint) – he is in fact secretly a replicant and to back this up, the director oddly inserts random Deckard daydreams of unicorns (outtakes from Scott’s 1985 Tom Cruise-starring Legend) and cuts the theatrical’s happy-ending short. Not only does this handicap the mystery to a degree, but it also shreds the intriguing yin-yang nature between Batty and Deckard: an artificial being becoming conscience with emotions he was never meant to develop versus the unempathetic human who makes a living gunning them down with little to no remorse (not to mention a scene that practically borders on sexual assault). Their climactic confrontation where Batty spares Deckard’s life loses it punch if it boils down to a confrontation between two robots. Deckard’s dumbstruck realization of the genuine humanity within an artificial construct is the close to his own character arc, from emotionless “robot” himself to a re-ignition of his own soul. Losing this to decisively answer a film debate robs the film of its own soul. [End of Spoilers.]

All in all, Blade Runner is a provocative film despite its issues. It’s more than a mere stepping stone in regards to science-fiction on film. While it doesn’t quite capture the greatness often attributed to it, it achieves the key fundamentals of a good science fiction endeavor by asking intriguing questions and opening the doors to honest thought and reexamination – as long as those thoughts don’t involve contemplations on sushi.