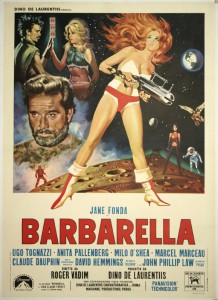

It will surprise no one when I state that Barbarella is far from being a cinematic masterpiece to be regaled by film historians as a significant illustration of motion picture production, but it was never meant to be. Rather, it is a sexy, silly, and fun diversion, not to be taken seriously and enjoyed as such. After all, any film featuring dialogue such as “de-crucify the angel…or I’ll melt your face!” may not quite serve as an ideal example of highbrow screenwriting. Instead, it is indicative of the breezy, ludicrous frivolity that encompasses the film.

On second thought, “ludicrous” may be an understatement. Following a sensual, zero-gravity striptease, secret space agent Barbarella (Jane Fonda) is entrusted by the President of Earth (Claude Dauphin) to track down the cryptic Durand Durand…

…who may have control of a positronic ray capable of plunging its victims into the fourth dimension. Soon after, a magnetic disturbance causes Barbarella to crash her spaceship onto an alien planet where she is promptly kidnapped by two little girls who force her to ski behind an ice-skating manta ray before tying her up and set upon by carnivorous demon dolls…and it only gets stranger from there.

Barbarella is a psychedelic trip, taking its cues from 1960’s excesses and hippie culture and delivering them on a multicolored platter with a recreational substance on the side. On its surface, the film has much in common with a science fiction retelling of Alice in Wonderland, complete with giant hookahs serving the “essence of man” (via a man literally swimming inside a hookah), a disturbing labyrinth filled with half-naked, crumbling creatures, and a kaleidoscopic chamber of dreams inhabited by the bisexual Dark Queen (Anita Pallenberg).

Yet what is more significant is that many of these episodes are demonstrative of why a film like Barbarella would strike a controversy of what is socially acceptable if released anew in today’s film industry, especially in consideration of its free love affirmations littered with nudity and drug use. Assuredly, it would receive an R rating (if not worse) amidst claims of sexism and gratuitousness; however, putting aside the fact that the film was truly a product of its time, these themes should not be misconstrued as anything more substantial than intended. Barbarella is free-spirited, not sleazy. Sure, it’s candidly erotic (such as the infamous scene where she out-pleasures the pleasure death organ, otherwise known as the excessive machine), yet Barbarella’s sexual proclivity is an indication of her liberated nature and never undermines the strength of her resolve.

Regardless, Barbarella was never intended to be a film that would provoke such debate. Beyond its fantastic flights of imagination, costume design, and Jane Fonda’s presence (though not necessarily performance), there is little to recommend in terms of quality film-making or subtext, but that’s not the point. Rather, its tongue-in-cheek, spontaneous atmosphere and inventiveness succeeds in presenting an indulgent, care-free distraction. It’s camp at its most absurd, with a catchy 60’s beat and ridiculous special effects (consisting of fireworks and lava lamps representing cosmic phenomena). In the end, Barbarella offers an enjoyable ride – as long as you don’t think about it too much.