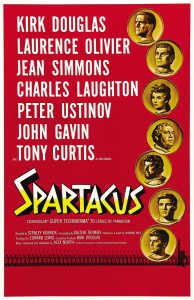

It’s hard to believe that Spartacus came out in 1960 – especially when viewing the three-hour plus restored version that was released in 1991. Debuting in the same year when the stricter Motion Picture Production Code gave Alfred Hitchcock strife over the much tamer shower scene in Pyscho, Spartacus is a violent affair featuring brutal gladiatorial combat, elaborate battle scenes leaving wakes of men, women, and children decaying in the open, and limbs getting sliced off in bloody, artery spewing displays. Despite a few impressive moments of action (particularly a slave revolt that closes its first act), Spartacus is a film that drags in the interns between and is more notable today not for the grandness of its product but rather for its single great contribution to the film industry by helping bring about the end of the McCarthy era blacklist in Hollywood.

Dalton Trumbo, Oscar-nominated screenwriter for films such as Kitty Foyle (1940), Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944), and A Guy Named Joe (1944), was one of the infamous Hollywood Ten blacklisted during the McCarthy Hearings in 1947 for his affiliation with the Communist party and for refusing to name names. Following an 11-month incarceration, he would continue to write screenplays over the next decade using various pseudonyms and fronts, winning two Academy Awards for Roman Holiday (1953) and The Brave One (1956) under the guises of Ian McLellan Hunter and Robert Rich respectively. Following a heated debate over selecting an “appropriate” front for his script for Spartacus, Kirk Douglas (who also served as the film’s executive producer) insisted on giving Trumbo his proper credit, an unprecedented move that would shake the industry out of the blacklist.

Yet, Spartacus‘ attacks on the McCarthy era were not limited to the politics of accreditation. The film’s subtext provides a blatant attack on the era, culminating in Laurence Olivier‘s Crassus demanding Spartacus’ followers list the names of their compatriots following the latter’s slave revolt throughout Rome. It’s an interesting theme that touches on the witch hunts and civil rights issues of the time but is glaring enough to spark the ire of director Stanley Kubrick who would later dismiss the film as “stupid moralizing.” Although the parallels are intriguing, the application is admittedly ham-fisted at times.

Spartacus‘ greatest strengths are showcased in its production values, incredible cinematography, and a few notable performances, including Peter Ustinov in the Oscar-winning role of the avaricious slave trader who buys Spartacus and Charles Laughton as the patriotic Roman senator that opposes Crassus’ tyranny. Kirk Douglas exhibits great physicality as Spartacus and the actor’s natural charisma helps strengthen the film, overlooking the fact that his facial expressions generally consist of a glaring stare for most of the film’s overlong runtime.

Despite some of the film’s failings, Spartacus would achieve far greater distinctions than its original intentions. The retrospective comparisons that can be drawn between Spartacus’ uprising for freedom and Douglas’ courageous bid against the Hollywood blacklist are compelling and if the film received no more accolades beyond its accomplishment against the blacklist, it would still leave behind a legacy to be admired.