Song of the South. Never has there been a more vilified or controversial entry in the entirety of the Disney canon – animated or otherwise. The very name brings up accusations of stereotyping, racism, and censorship. With Disney having pulled the film out of availability in the United States since the mid-80’s, only its most vile allegations survive as an unfortunate legacy to a mass public that has never seen the film.

But is there any truth to be found in these accusations? Would the beloved Walt Disney, creator of such endearing characters as Mickey Mouse, Dopey, and the crows from Dumbo (okay, bad example), ever produce an outright racist or ethically demeaning film?

Let’s face it – any discussion of Song of the South can be overwhelmed by the film’s controversies. Hell, many may condemn me for simply giving it a “platform” regardless of what is written or stated. On the rare occasions when the film is discussed, judgments usually mirror the condemnations lest there be any negative social repercussions. The “smart” move would be to avoid it altogether; yet, to ignore it would also involve overlooking the great impact the film had in cinematic history. It may be surprising to some (or even loathsome for many to accept) that despite its general damnation, Song of the South marked a huge step forward in many areas including African American representation in film.

How the hell is that possible given the general outrage? Well, before we address that subject in more detail, let’s take an objective look at the film as a whole. After all, this is a picture that not only earned a couple of Academy Awards, has some of the most recognized songs in Disney history, and inspired one of the most popular Disney theme park attractions, Splash Mountain, but was also Walt Disney’s first serious foray into live-action (The Reluctant Dragon “documentary” aside).

Walt Disney’s Song of the South |

Song of the South is based on Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus children’s book series which featured an assorted collection of African-American folktales. The tales themselves, which often focused on the adventures of the clever Br’er Rabbit, were related through the title character of Uncle Remus, a kind, old former slave. Harris, who had heard many of these oratory tales around a campfire as a child, began to document and preserve the stories which were first published in 1880.

Song of the South is based on Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus children’s book series which featured an assorted collection of African-American folktales. The tales themselves, which often focused on the adventures of the clever Br’er Rabbit, were related through the title character of Uncle Remus, a kind, old former slave. Harris, who had heard many of these oratory tales around a campfire as a child, began to document and preserve the stories which were first published in 1880.

Although Song of the South exhibits the animated retelling of three Remus stories, the film’s narrative alternatively focuses on the character of Uncle Remus himself, exploring the man behind the folktales and the effect his didactic stories have on the children that hear them. What could have only served as throwaway live-action framing sequences for the three short cartoons (indicative of the other Disney package features being released at the time) instead springs to life with the charming, efficacious performance of James Baskett as Remus.

Set during the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, the film begins with a young city boy, Johnny (Bobby Driscoll), being shipped off to a Georgian family plantation. Believing that his work as a controversial news editor has placed his family at risk, his father (Erik Rolf) figures that the plantation would be a safe refuge for his wife (Ruth Warrick) and son and mollifies his absence by astounding the boy with anecdotes about Uncle Remus (Basket), a former slave with a panache for incredible folktales.

Set during the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, the film begins with a young city boy, Johnny (Bobby Driscoll), being shipped off to a Georgian family plantation. Believing that his work as a controversial news editor has placed his family at risk, his father (Erik Rolf) figures that the plantation would be a safe refuge for his wife (Ruth Warrick) and son and mollifies his absence by astounding the boy with anecdotes about Uncle Remus (Basket), a former slave with a panache for incredible folktales.

Mourning the loss of his father, Johnny opts to run away; however, a chance encounter en route with Remus changes his mind as he becomes enamored with the tales of Br’er Rabbit (Johnny Lee; Baskett), a cunning forest critter whose own runaway attempt is thwarted by the devilish Br’er Fox (Baskett) and Br’er Bear (Nick Stewart). Soon, a deep bond forms between Remus and the boy – a bond that aggravates his mother who views the lowly Remus as a bad influence. After forbidding Johnny to see Remus again, the boy becomes distraught and ends up getting accidentally gorged by a bull!

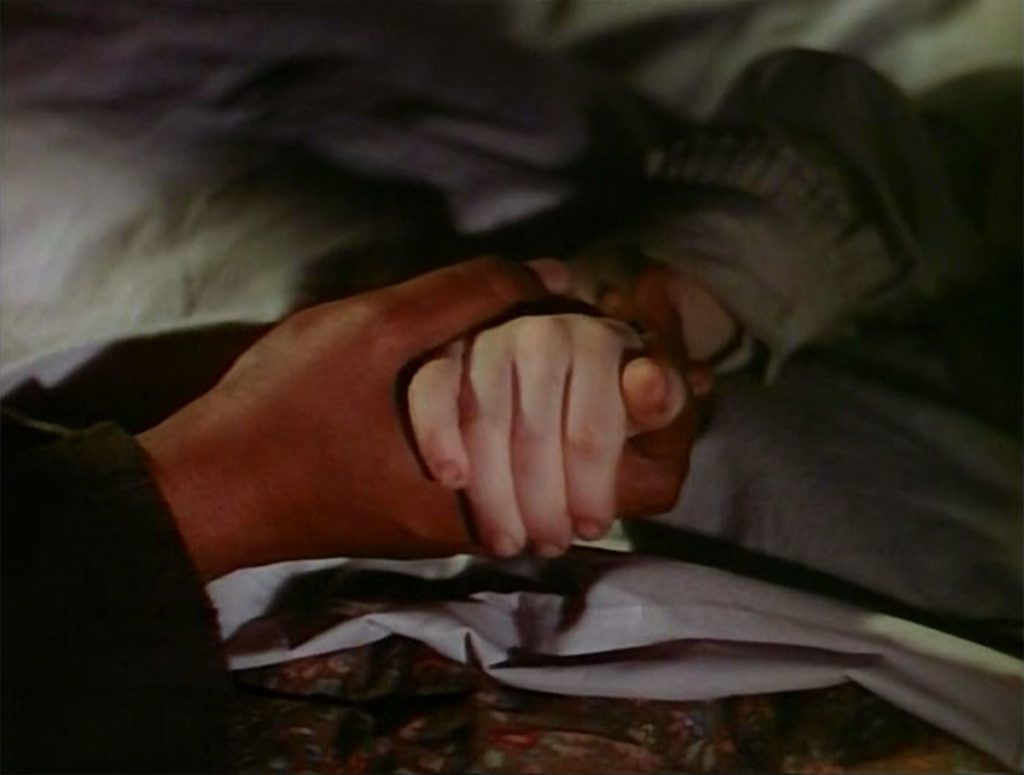

With the boy’s life on the line, his mother, realizing her prejudice has brought about disaster, accepts Remus into the family home in an attempt to console the child. Upon hearing Remus’ stories by his bedside, the child slowly awakens from his fever dream, is reunited with his father, and the song ends happily ever after.

Song of the South has three primary elements that elevate it to a classic: excellent songs and music (naturally), incredible visuals and special effects, and the extraordinary performance of James Baskett.

The songs, particularly “How Do You Do?,” “Everybody Has a Laughing Place,” and the Oscar-winning “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,” are exemplary, providing some of the best output from the Disney Studios during Walt’s lifetime. Enduring with a contagious quality that powers the joy found during the animated sequences, it’s no wonder that the Splash Mountain attraction heavily showcased these specific numbers.

The film’s three cartoon segments are equally indicative of the best animation from the Studio during their package feature era, representing their most shining effort between 1942’s Bambi and 1950’s Cinderella. The shorts, adaptations of three of the most well-known Remus tales—”Br’er Rabbit Earns a Dollar a Minute,” “Tar-Baby,” and “The Laughing Place”—are the highlights of the film and quite faithful to the original fables, albeit with the whimsical Disney slapstick touch.

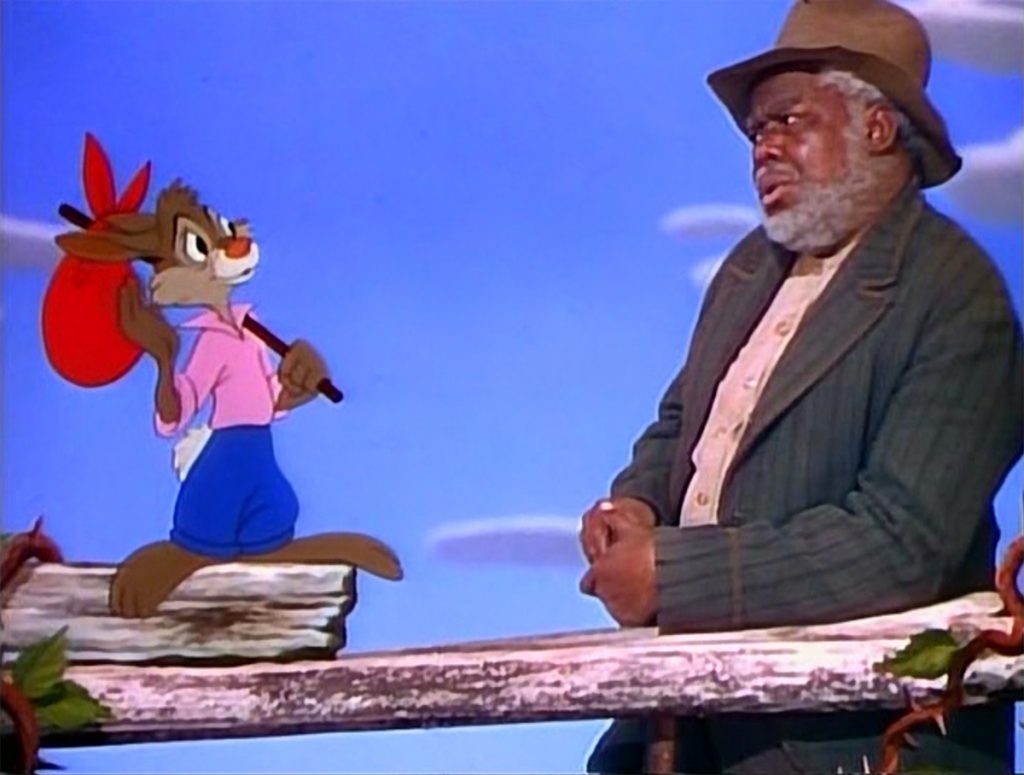

Of the three, the first two are the primary stand outs specifically due to the live-action interaction between Remus and the animated critters. These interactions not only serve as excellent bridging material to introduce the tales themselves but they also emanate a true sense of wonder, featuring what may be Disney’s most adept blend of live-action and animation until Who Framed Roger Rabbit over forty years later (Mary Poppins and Bedknobs and Broomsticks notwithstanding).

Whether Uncle Remus is singing with Br’er Rabbit, enjoying a lazy pipe and fishing with Br’er Frog, or taking a stroll on a “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” spring day, you don’t get the impression that it’s an actor in front of a screen or a stage, oddly gazing in wild directions of where the animated characters should be. On the contrary, he looks like he belongs there. Part of that is the due to James Baskett’s performance which outright sells the concept.

Baskett effectively captures the spirit of Uncle Remus, radiating a joyous frivolity that beckons you to hang onto every notation of his storytelling (dated dialect aside); yet, there is a deeper layer to his character beyond that of a playful fabulist. His connection with the young boy has a genuine authenticity, providing a strong backbone to the picture and empowering the bedside ending that could have easily come across as hokey or predictable otherwise. I mean, let’s face it, a child on the verge of death being brought back from the brink due to the power of friendship and bunny stories? It’s the very type of cliche that Disney has become infamous for yet Baskett’s nuanced and touching approach to the scene wholly trounces the criticism. His Honorary Academy Award, the first Oscar for a black male performer, “for his able and heart-warming characterization of Uncle Remus, friend and story teller to the children of the world” is thoroughly deserving and underscores the great tragedy that it may be lost in time due to the film’s unavailability.

Nevertheless, the film does have a few major issues (excepting its notorious criticisms). Bobby Driscoll and Luana Patten‘s performances, although both adequately capable, are marred by the script’s tendency to have them break down and cry in almost every scene they appear in! By the film’s climax, I was doubting that Driscoll was bedridden from the bull attack; surely, the culprit must have been dehydration due to his constant waterworks. Admittedly, a child breaking down due to heartbreak can be utilized as a compelling narrative tool but Song of the South takes it to an extreme.

His introductory scene: Cry Face…

…followed by another Cry Face…

…followed by another Cry Face…

…followed by: Extreme Cry Face!

…followed by: Extreme Cry Face!

Soon, his constant weeping and sobbing become infectious and the girl joins in…

Soon, his constant weeping and sobbing become infectious and the girl joins in…

Perhaps a more apt title would have been Sobs of the South! Heck, there’s even an extended minute-long scene of Driscoll whimpering through the woods as the score erupts with a grating “Nyah Nyah Nyah Nyah Nyah Nyah!” childhood teasing theme! Luckily, both performers would be served better in their many follow-up Disney projects such as South‘s spiritual sequel, So Dear to My Heart (1949), and Driscoll’s starring roles in Treasure Island (1950) and Peter Pan (1953).

Perhaps a more apt title would have been Sobs of the South! Heck, there’s even an extended minute-long scene of Driscoll whimpering through the woods as the score erupts with a grating “Nyah Nyah Nyah Nyah Nyah Nyah!” childhood teasing theme! Luckily, both performers would be served better in their many follow-up Disney projects such as South‘s spiritual sequel, So Dear to My Heart (1949), and Driscoll’s starring roles in Treasure Island (1950) and Peter Pan (1953).

Disappointingly, some of the more fascinating elements of Song of the South are either downplayed or not fully explored to their potential. The father’s risky news ventures, for instance, are never specifically stated or explained. Given the time period and the dangers alluded to, it would have been an intriguing subplot – especially if it allowed an opportunity to support the film’s theme of class divisions (more on this later); however, as most of the movie plays out from his son’s point of view, its excision may be justified.

On the other hand, the mother’s relationship with her son leaves much more to be desired. With the exception of the bull and some neighborhood bullies, she comes across as the film’s primary antagonist. Considering that the kid has lost his father leaving him feeling abandoned and alone in an unfamiliar setting, her attempts to rip him away from the one connection he makes in Uncle Remus—a connection built up by his absent father, no less—seem unfathomably harsh. When the boy tries to supplement his loneliness with a puppy, she forbids that as well! What? Is a plantation no place for a puppy?! How cruel is this woman?

Racist Songs from the South? |

Song of the South was doomed from the beginning. No matter how the subject matter was portrayed it would have sparked the ire and derision from many political and ethnic camps. Regrettably, no examination of Song of the South can avoid the film’s scandalous reputation. The way some people make it sound is as if Walt Disney essentially made a fun-filled, animated musical romp about slavery. Worse still, many who levy accusations against it haven’t had the opportunity to actually watch the film (and many who have the chance simply refuse to watch it on “principle”) – a singular pet peeve of mine as I thoroughly believe that it is vital to wholly experience a project before passing judgement let alone lambasting it (no matter if the takeaway is positive or negative). For example, the movie Twilight has garnered a horrific notoriety but what would it say about one’s character or position if they were to condemn it without actually seeing it for themselves?

Perhaps the most flagrant example of this in regards to Song of the South was the NAACP’s denouncement of the film when it was originally released. In a national statement, the organization proclaimed “that in an effort neither to offend audiences in the north or south, the production helps to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery. Making use of the beautiful Uncle Remus folklore, Song of the South unfortunately gives the impression of an idyllic master-slave relationship which is a distortion of the facts.” A harsh criticism to be sure and one that is plagued by two crucial issues: 1.) the film does not feature slavery as it takes place after the Civil War and, 2.) the statement was based on hearsay as the writer had not actually seen the film!

Nevertheless, it’s an impression that has hung over the film ever since—even modern day reviewers make the error—and one that is largely Disney’s fault. Despite early suggestions that it should be included, a simple date or opening text crawl making it crystal clear that the story takes place after the Civil War would have done wonders in nullifying many of the most severe attacks. After all, when Uncle Remus decides to pack up and move to Atlanta during the film’s third act, it is undeniable that he is a freeman rather than a runaway.

The other major issue raised is the film’s use of what have been described as Uncle Tom-like dialects. Yes, the film does sport some stereotypical black dialects though, arguably, it does not do so in an excessively derisive manner. In consideration of the time period, had Disney gone in the other direction and removed all such offending dialects, it may have been equally, if not more voraciously, scorned for whitewashing history. It was a no-win situation and one that is understandably heightened when viewed through today’s more refined lens.

To be fair, the lower class white family living on the plantation also use similarly dated dialects and are equally subservient to the richer plantation family. Unlike the more positive presentation of the black families in the film, the boys from the low-class white household are absolute white trash – little monsters who revel in drowning puppies (the antithesis of Remus’ respect for animals), physically abusing their sister (Patten), and, at one point, violently attempting to club little Johnny in the back of the head (thankfully, Remus intervenes just in time).

The divisions in Song of the South aren’t solely of white versus black but one of higher class versus lower class. Part of the mother’s disdain for Remus is due to this conceit. This can be inferred when Johnny wants to invite Luana Patten to his fancy birthday party only to get reflexively dismissed by his mother. When we see the party, it’s a multi-colored indulgent affair of bright suits, frilly laces, and haughty extravagance. Yet, when Johnny is injured, the only party keeping candlelight vigil outside are the black plantation workers.

Regardless, it must be considered that many films from this era were far more egregious in respect to depictions of African-Americans in film – especially when it comes to dialect. Case in point, 1939’s Gone with the Wind, which coincidentally also featured South‘s Hattie McDaniel for which she won an Oscar (the first black female ever to do so). What damns Song of the South and gives pass to Wind (a film that actually featured slavery) was the intended audience and tone – Gone with the Wind is by no means regarded as a family picture.

Yet, what sets Song of the South apart from a majority of films from the era is its intent. This isn’t a film that resolves to subjugate African-Americans in favor of white superiority or any other such despicable attributions (compare it to 1915’s The Birth of a Nation for such brutality). Song of the South was, I dare say, ahead of its time: a mainstream release from a major studio starring a black actor in the mid-1940’s that became the most successful film of the year, earning the actor the highest accolades. Uncle Remus isn’t depicted as a silly stereotype or a bumbling imbecile; rather, like the Br’er Rabbit of his fables, he is the single most intelligent character in the film – regardless of the dated or dubious dialect.

Moreover, the film is about the bridging of gaps between class, race, and even family. This single frame, above all else, represents the very thesis of the film – the emblematic notion that the innate truths of stories and creativity have the power to connect even the most unlikely people.

Yes, Song of the South may be dated and even problematic from today’s perspective but its positive, hopeful message isn’t one intent on propagating racism or bigotry but rather a message of unity. Whether in context of the story’s time frame or the date of the film’s release, this is a message that should resonate. Is it flawed in presentation? Sure. Could it have been done better? Possibly (one would expect that if first produced and released today, such dated attributions would be excised). Does Johnny’s Cry Face grate on one’s nerves? Definitely. Yet, in the end, Song of the South should be celebrated or, at the very least, utilized as an opportunity for learning. We cannot “improve” history by turning a blind eye to the past or castigating older works of art based on modern surface-level issues. To do so would be an context-less, non-provocative look at the past which leaves us more susceptible to repeat its most inhumane errors.

Yes, Song of the South may be dated and even problematic from today’s perspective but its positive, hopeful message isn’t one intent on propagating racism or bigotry but rather a message of unity. Whether in context of the story’s time frame or the date of the film’s release, this is a message that should resonate. Is it flawed in presentation? Sure. Could it have been done better? Possibly (one would expect that if first produced and released today, such dated attributions would be excised). Does Johnny’s Cry Face grate on one’s nerves? Definitely. Yet, in the end, Song of the South should be celebrated or, at the very least, utilized as an opportunity for learning. We cannot “improve” history by turning a blind eye to the past or castigating older works of art based on modern surface-level issues. To do so would be an context-less, non-provocative look at the past which leaves us more susceptible to repeat its most inhumane errors.

In these regards, just this month, actress Whoopi Goldberg attended the D23 convention and spoke up in support of making the film publicly available. “I’m trying to find a way to get people to start having conversations about bringing Song of the South back,” she said. “So we can talk about what it was and where it came from and why it came out.” She also pardoned Dumbo‘s aforementioned controversial crows, stating that she wants “people to start putting crows in the merchandise, because those crows sing the song in Dumbo everybody remembers.” How ironic would it be if the film whose main theme of bridging gaps—a film that has unfortunately gone on to divide so many—would once again bridge gaps to ensure its rerelease?

Man-Card Retribution |

I just gave a positive review to the most controversial Disney movie. If that doesn’t deserve a man-card, I don’t know what does…

Man-Card Verdict: +1

Random Afterthoughts… |

For a character that is supposedly impossible to catch, at least according to Br’er Fox, it is funny to note that Br’er Rabbit gets caught in all three of the animated sequences. By the third sequence, the film doesn’t even take the time to show how he was ensnared!

Ever think that Splash Mountain sported a very distinctive look? It’s straight out of the film.

Gees, between this film, Old Yeller, Pollyanna, and Johnny Tremain, was it a trend for period Disney movies to feature children being hurt or maimed in debilitating accidents? Whether being gorged by bulls or feral hogs, becoming paralyzed by falling out of trees, or getting their flesh scorched by molten metal, some of the Studio’s early work depicted a sobering sense of consequence rarely seen in today’s children’s entertainment.

If there is one positive aspect to come from the Walt Disney Company’s public withdrawal of the film it’s that no cheap, derivative, or direct-to-video sequel was ever produced.

Join us next week when Mickey Mouse faces his largest foe in “The Brave Little Tailor” (1938). For more Default Disney, click here, and for more information on Song of the South, I’d recommend the excellent songofthesouth.net.

Join us next week when Mickey Mouse faces his largest foe in “The Brave Little Tailor” (1938). For more Default Disney, click here, and for more information on Song of the South, I’d recommend the excellent songofthesouth.net.